The Lost Diagrams of Walter Benjamin, edited by Helen Clarke & Dr. Sharon Kivland. This first edition was published by MA BIBLIOTHÈQUE, London, and presented at ‘MISS READ: Berlin Art Book Fair & Festival’, Haus Der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany in 2018. This publication is now in its second edition print run, and is part of the ‘Anthologies, Collections & The Conceit of the Conceptual Series — which includes anthologies, collected essays, artist's and writer's projects, at the editor's whim. Book covers are in varying attractive shades of pink.

Synopsis: In A Berlin Chronicle (c. 1930), Walter Benjamin describes his autobiography as a space to be walked (indeed, it is a labyrinth, with entrances he calls primal acquaintances). The contributors to The Lost Diagrams respond to the invitation to accompany Benjamin in reproducing the web of connections of his diagram, which, once lost (he was inconsolable), was never fully redrawn. They translate his words into maps, trees, lists, and constellations. Their diagrams, after Benjamin, are fragments, scribbles, indexes, bed covers, and body parts. Subjectivities sharpen and blur, merge and redefine, scatter and recollect. Benjamin writes:

‘I was struck by the idea of drawing a diagram of my life, and I knew at the same moment exactly how it was to be done. With a very simple question I interrogated my past life, and the answers were inscribed, as if of their own accord, on a sheet of paper that I had with me. A year or two later, when I lost this sheet, I was inconsolable. I have never since been able to restore it as it arose before me then, resembling a series of family trees. Now, however, reconstructing its outline in thought without directly reproducing it, I should rather, speak of a labyrinth. I am not concerned here with what is installed in the chamber at its enigmatic centre, ego or fate, but all the more with the many entrances leading to the interior. These entrances I call primal acquaintances; each of them is a graphic symbol of my acquaintance with a person whom I met, not through other people, but through neighbourhood, family relationships, school comradeship, mistaken identity, companionship on travels, or other such- hardly numerous- situations. So many primal relationships, so many entrances to the maze. But since most of them- at least those that remain in our memory -for their part open up new acquaintances, relations to new people, after some time they branch off these corridors (the male may be drawn to the right, female to the left). Whatever cross connections are finally established between these systems also depends on the inter-twinements of our path through life’.

Essays by Helen Clarke, Sam Dolbear, & Christian A. Wollin.

Contributors: Cos Ahmet, Alberto Alessi, Sam Ayres, Patrizia Bach, Martin Beutler, Riccardo Boglione, Vibe Bredahl, Pavel Buchler & Nina Chua, Emma Cheatle, cris cheek, Kirsten Cooke, Anne-Marie Creamer, Amy Cutler, Vincent Dachy, Matthew Dowell, Joanna Leah Geldard, Theresa Goessmann, Michael Hampton, Ronny Hardliz, Miranda Iossifidis, Joe Jefford, Dean Kenning, Tracy Mackenna, Bevis Martin & Charlie Youle, John McDowall, Katharine Meynell, Paul O’Kane, Hephzibah Rendle-Short, Mark Riley, Katya Robin, Hattie Salisbury, Isabella Streffen, Stefan Szczelkun, George Themistokleous, Monique Ulrich, Emmanuelle Waeckerle, Matthew Wang, Julie Warburton, Alexander White, Lada Wilson, Louise K. Wilson, Mark Wingrave, Mary Yacoob.

MA BIBLIOTHÈQUE is a not-for-profit project by the artist and writer Sharon Kivland in 2015. The publications are modest yet attractive, and constitute her library, based on her purchase of a hundred ISBN numbers. In her role as The Editor, she invites authors she considers to be good readers, whom she would like to house in her library or to become her library, inhabited.

Helen Clarke is a Heritage Consortium doctoral student, supervised by both Casey Orr (Leeds Beckett University) and Dr. Sharon Kivland an artist, writer and a reader in Fine Art, Sheffield Hallam University.

Search for a Diagram, review text by David Briers

Described by Ian Sansom as 'a stationery obsessive', Walter Benjamin's love of fountain pens, his precious use of notebooks and scraps of paper, and his characteristically minute handwriting are far from incidental aspects of his praxis. The physical and indexical nature of his surviving archive has become as influential in recent years as the ideas embodied therein. As Susan Buck-Morss correctly says, quoted on the cover of this book: 'The capacity of Walter Benjamin's work to inspire others is extraordinary.' A new generation of artists, as Helen Clarke remarks, is preoccupied with 'the re-use and re-presentation of Benjamin's works', notably including Brian Ferneyhough's remarkable 2004 opera Shadowtime.

In his 1932 text 'Berlin Chronicle', Benjamin refers elliptically to a 'diagram of his life' that he had made with ink on paper, but which he had lost a year or two later. The diagram (if it ever existed) was never recovered, and the intimations Benjamin gave to its nature were scant: 'resembling a series of family trees' or 'a labyrinth'. Co-editor Helen Clarke made open calls and invited submissions from contributors to 'translate (Benjamin's) words into maps, trees, lists and constellations'. This book offers an edited selection of those received.

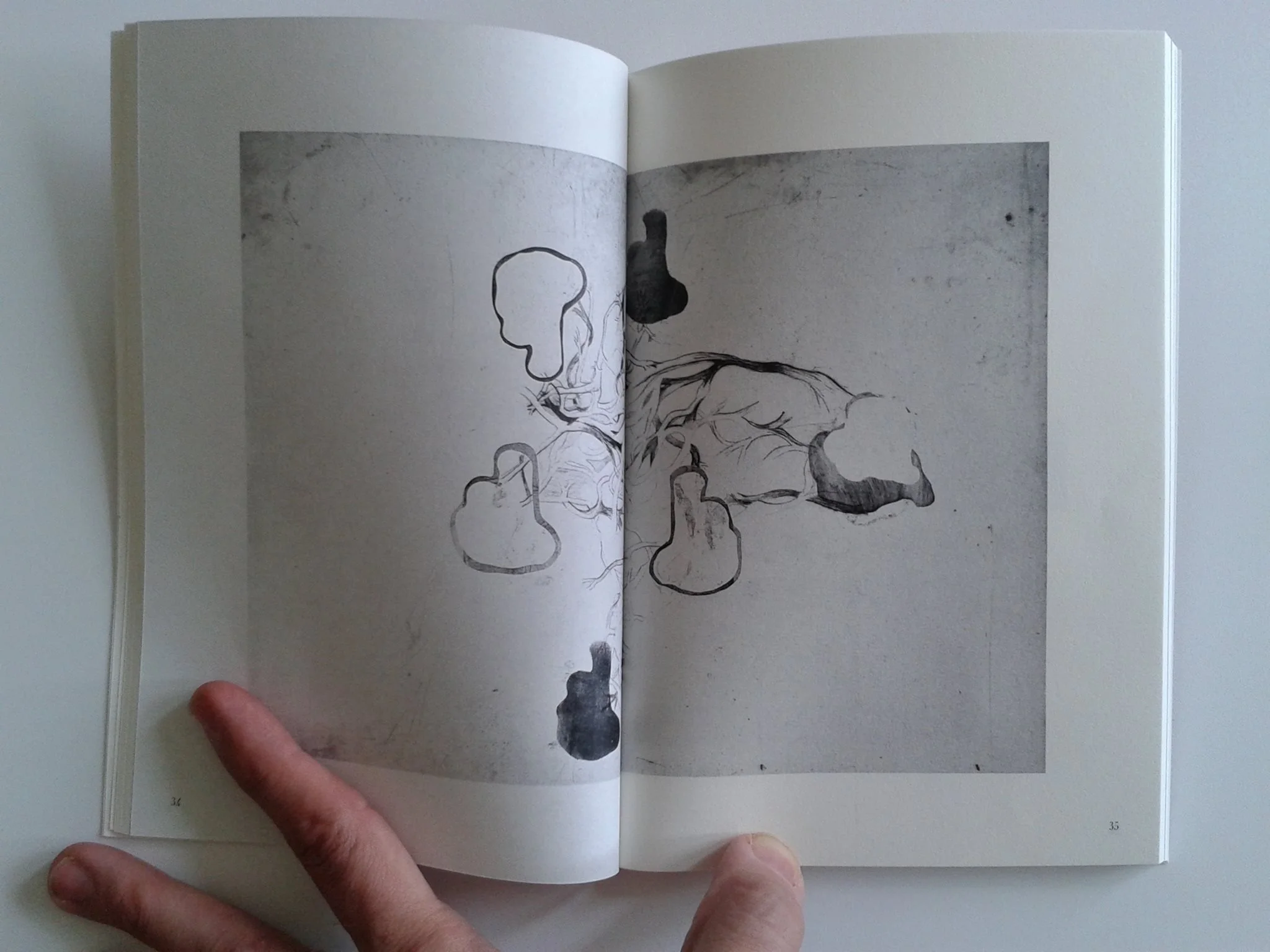

The 43 contributors of these visual translations include artists, poets, writers, bookmakers and a composer, though no further information is given other than their names. Some will be familiar to the follower of this kind of artists' printed matter, many not. There are also three illuminating prefatory essays. The 'diagrams' themselves (some refer specifically to Benjamin's life history, most don't) include street maps, constellations of words or shapes, a drawing on a used envelope, mysteriously vegetal and occultist drawings, a management training diagram, linear texts winding themselves around a rock garden and a maze, a found pricelist of office supplies and a drawing of an architectural head.

This might have been a deluxe portfolio of drawings or an exhibition. But in its chosen much smaller soft-back format, its portability, and unhierarchical nature more astutely mirror the 'fragmentary and essayistic' nature of Benjamin's later praxis, even if some contributions suffer in legibility. In her essay, Clarke touches on 'the recent resurgence of interest in the non-precious artist's book as a form ...' and, in terms of its variegated graphic content, the overall feel is very much that of the Assembling Magazines culture of the 1970s in which mail artists and others were invited to submit the same number of photocopies of a new work to a central collating and distributing editor.

For those bitten by the Benjamin bug, the allure of the mischievously misleading title of this book is irresistible. It is no wonder that the first run of the publication sold out quite rapidly. I will unselfconsciously put this publication on my bookshelves alongside works by or about Benjamin, rather than with the artists' books.

Art Monthly; London Issue 414, March 2018. David Briers is an independent writer & curator based in West Yorkshire.

Images: Cover for ‘The Lost Diagrams Of Walter Benjamin’, edited by Helen Clarke & Sharon Kivland; Two-page spread of Cos Ahmet’s diagram contribution ‘System For A Lost Identity’ from the publication; Detail of ‘System For A Lost Identity’ (2018), drypoint etching and mono print on 330gsm Somerset Satin paper.